| |  |

|

Welcome To

VIETNAM WAR

The Vietnam War topped the list of concerns of Murray County families in the 1960s. The military draft threatened to disrupt the lives of most men/boys from age 18 upwards. Scores of Murray men served in Vietnam. Four were killed there.

This section of the museum is devoted only to the Vietnam War's impart on Murray lives. Most of the material initially posted in this section first appeared in The Chatsworth Times during the fall of 2010. The articles were written and copyrighted by Herman McDaniel, who retains all rights to them.

The topics: The Vietnam War, a Brief Retrospective; The Vietnam Memorial Wall; First Murray Soldier to Die in ‘Nam: Jimmy Cagle; Second to Die: Jerry Jordan; Third to Die: Gary Cruse; Fourth (and last) to die: Raymond Beam.

Much information appears in the museum that was not included in the newspaper.

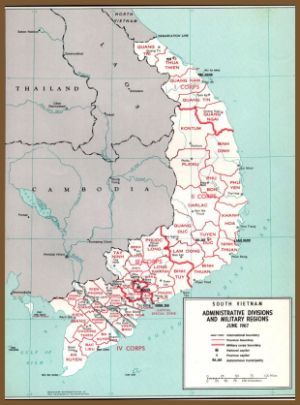

Tap To Enlarge!

The Vietnam War Divided Americans

© Copyright 2010, Herman McDaniel

Americans Remember Words and Images

The mere mention of the Vietnam War calls to mind photographs and television images that were burned into viewers' psyche during that long nightmare.

Certain words and phrases from those years also conjure up memories and images for those who lived through that era: hippies; sexual revolution; free-love; the drug culture; draft dodgers; peace symbols; the establishment; the puzzle palace; Disney Land East; Berkeley; Kent State University, etc.

One of the earliest shocking images that Americans saw on television was broadcast in 1963, a Buddhist monk setting himself on fire in public, then burning to death without flinching, dying to protest the policies of the South Vietnamese government. During the course of the war, several others died in similar fashion, some in the United States. In 1965 an American Quaker poured kerosene on his body, then set himself ablaze underneath the Pentagon window of Secretary of Defense McNamara.

The anti-war protest rallies seemed to be constantly on television screens and newspaper front pages, varying mainly by location, intensity, and number of demonstrators present.

The photo of a South Vietnamese officer shooting a suspected Viet Cong boy shocked the world. Photographer Eddie Adams received a Pulitzer Prize for this nightmarish image. The execution was also captured on video that shocked television viewers around the world.

Although many photos of napalm victims were published, perhaps the one most people of that era remember best is from June 1972 depicted a terrified 9-year-old girl, nude, running from her village. Photographer Nick Ut had been in the village and was just walking away when the planes dropped four regular and four napalm bombs. He photographed the fleeing girl, then gave her water hoping to cool her down, before rushing her to a military hospital some ten miles away. Medics there treated the girl and she recovered. Kim Phuc's family and "Uncle Nic" became close and enjoyed regular contact for many years. For this heart-stopping photograph Nick Ut was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

A Statistical Update

The Department of Defense on August 5, 2010, issued an updated accounting of American casualties associated with the Vietnam War to reflect events up to that date. The revised numbers indicate that 58,267 Americans were killed in action or died of other causes in Vietnam. Another 303,644 were wounded in action, with 153,303 requiring hospitalization. Even though the fate of many Americans once classified as Missing in Action has been resolved, 1,711 still remain on that worrisome list.

Reliable statistics and information about Americans who died in Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand continue to remain either elusive or unreliable. Because the United States was not supposed to be fighting in those countries at the time that American soldiers died there, their military records indicate that they were killed in Vietnam.

A very recent event underscores just how sensitive deaths in countries other than Vietnam really were. On September 21, 2010, President Obama posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor to Air Force Chief Master Sergeant Richard L. Etchberger, who had sacrificed his own life in order to load three of his wounded airmen into an evacuation helicopter in Laos, March 11, 1968. The explanation given for the 30+ years delay in making the award was that no Americans were supposed to be fighting in Laos when Sergeant Etchberger died.

The revised Department of Defense statistics cited above estimated that U. S. Forces killed 1.1 million enemy combatants, North Vietnames and Viet Cong, in the Vietnam War.

It also estimated that 266,000 South Vietnam fighters died.

Estimates of the number of civilian deaths vary so much as to be virtually meaningless. Millions of civilians died in the region during the period.

How Did the United States Get Involved?

Prior to World War II much of southeast Asia was governed by European countries who claimed the various countries as colonies. France held claim to several countries, including Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Seeking independence, various groups challenged France militarily. In Vietnam, the decisive battle was at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The French suffered a comprehensive defeat, described by a military historian as "the first time that a non-European colonial independence movements had evolved through all the stages from guerrilla bands to a conventionally organized and equipped army able to defeat a modern Western occupier in pitched battle."

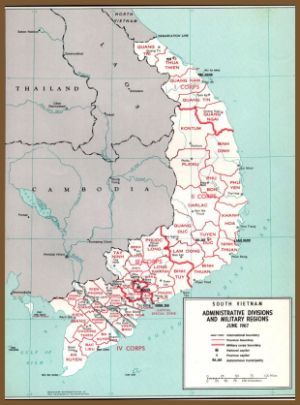

France, following that humiliating defeat, agreed to withdraw from its former Indochinese colonies, and the 1954 Geneva Accords partitioned Vietnam into two. The accords made clear that the partition was intended to be a temporary measure until internationally supervised free elections could be held in 1956. Those elections were never held and the two were soon recognized as separate countries or states. In the north, Ho Chi Minh controlled the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, with Hanoi as the capital. The south became officially the State of Vietnam, but was called South Vietnam. The capital was Saigon.

Lyndon Johnson had become President of the United States upon the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963. The United States Congress, on August 7, 1964, passed a joint resolution that gave Johnson authorization to use conventional military force in southeast Asia, without having Congress formally declare war. Known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, this legislation amazingly was passed in the House of Representatives by a vote of 416 to zero.

The Senate vote was nearly as lopsided but the remarks made by the two dissenting votes deserve to be heard as a matter of historical debate. The Congressional Record covering debate of August 6 and 7, 1964, recorded their objections as follows:

Mr. Gruening: (Ernest Gruening, Democrat, Alaska) "... Regrettably, I find myself in disagreement with the President's Southeast Asian Policy...The serious events of the past few days, the attack by North Vietnamese vessels on American warships and our reprisal, strikes me as the inevitable and foreseeable concomitant and consequences of the U. S. Unilateral military aggressive policy in Southeast Asia...We now are about to authorize the President if he sees fit to move our Armed Forces...not only in South Vietnam, but also into North Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and of course the authorization includes all of the rest of the SEATO (South East Asia Treaty Organization) nations. That means sending our American boys into combat in a war in which we have no business, which is not our war, into which we have been misguidedly drawn, which is steadily being escalated. This resolution is a further authorization for escalation unlimited. I am opposed to sacrificing a single American boy in this venture. We have lost far too many already..."

Mr. Morse: (Wayne Morse, Democrat, Oregon) "...I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake in subverting and circumventing the Constitution of the United Sates...I believe this resolution will be a historic mistake. I believe that within the next century, future generations will look with dismay and great disappointment upon a Congress which is now about to make such a historic mistake."

This legislation was brought about because the Congress had been misinformed about two relatively minor incidents in the Gulf of Tonkin. On August 2, 1964, three North Vietnamese Navy torpedo boats attempted to get close enough to the USS Maddox for their torpedo fire to be effective against that vessel. They reportedly fired all of their torpedoes and some 14.5 mm machine-gun fire. The torpedoes all missed their target and the attackers turned to flee the scene. American jet fighters appeared and fired Zuni rockets at the fleeing boats, scoring no hits. The jet pilots then fired 20 mm. cannons, damaging all three torpedo boats.

Two days later two American vessels reported that they were under attack by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. Hanoi immediately insisted that the second incident had not happened. Unfortunately Hanoi's denial was considered false for more than 40 years–until 2005, when an internal National Security Agency (NSA) historical study was declassified and made public. That finding, referring to the reported second attack of August 4, 1964, stated: "It is not simply that there is a different story as to what happened; it is that no attack happened that night . . . In truth, Hanoi's navy was engaged in nothing that night but the salvage of two of the boats damaged on August 2."

Decades later audio tapes recorded during the Johnson Administration were made public. On one recording President Johnson told Secretary McNamara that he was not certain that the Gulf of Tonkin incident used to get Congress to approve America's incursion into southeast Asia had ever occurred.

How the Vietnam War Was Different

Each war is remembered by things that set it apart from other wars. The Vietnam War separated Americans as no other except the Civil War ever had. Vietnam was the first war that was beamed daily into American homes via television.

Americans who died in earlier wars usually were buried near where they died. In Vietnam the military retrieved tens of thousands of bodies and quickly transported them home to families for burial. This required an amazing amount of manpower and effort.

In Vietnam the Viet Cong used networks of tunnels to conceal the movement of fighters, weapons, ammo, and supplies great distances. Some of the tunnels contained hospitals and medical supplies, food caches, weapons and ammo.

The Viet Cong forced civilians, often children, from nearby villages to build sections of each tunnel. One system ran for more than 125 miles underground. It has been strengthened to withstand explosions and bombings and had air systems to protect against poison gas. American officials revealed after the war that some of the tunnels actually ran beneath U. S. facilities.

To cope with this innovative military situation, American soldiers had to physically enter the tunnels. Smaller American soldiers, equipped with pistols, knives, flashlights, and gas masks entered the tunnels and crawled their entire length. Known as "tunnel rats," they were considered a special breed of soldier unknown before the Vietnam war.

American forces relied heavily on saturation bombing in this war. In the tiny province of Quang Tri alone (where the two Vietnams were separated by the Demilitarized Zone), American planes dropped more bombs than the total amount of ordnance used in Europe in World War II. After the war, experts reported that Quang Tri was the target of the heaviest bombing campaign in the history of the world. Others argue that this distinction belongs to the tiny nation of Laos, also a target of American planes.

The Vietnamese reported, also after the war ended, that Qiang Tri's two largest towns had been so completely destroyed, that not a single building remained useable. They also said that, of the more than 3,000 villages across that province, only 11 remained after the war. Because the United States had also sprayed the defoliant Agent Orange across that province, most of the population had fled.

U.S. officials have also concluded that the bombing and artillery used in their attempt to destroy the Citadel at Qiang Tri in 1972, represented more than eight times the velocity of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1954.

Public Support Fades

Many draft-age men who opposed the war and wanted to avoid being forced to serve, simply went to Canada or Sweden and disappeared.

College students organized and led nonviolent anti-war protests, questioning America's involvement in southeast Asia. Initially these were small, local rallies, but as American learned more about the conduct of the war, the rallies grew into huge gatherings. As early as November 1965, more than 35,000 protestors marched in Washington. More than 50,000 demonstrated at the Pentagon October 21-23, 1967. Protests across America as well as in London, Paris, and Rome became commonplace. So did crowds of tens of thousands.

Some dissenters started to turn in their draft cards at rallies. Next they began to publicly burn them, in obvious violation of the law.

People whose names were known in virtually every American home started to voice their support for, and participate in, the anti-war rallies. Dr. Martin Luther King persuaded countless people to support the anti-war movement. So did Dr. Benjamin Spock.

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan became even better known for their protest music. Abbie Hoffman, Jane Fonda, and Timothy Leary also worked extensively with the protest organizers.

Main stream Americans took notice when six veterans of the Vietnam war marched together in a peace demonstration in 1967. The newly formed National Association of Vietnam Veterans Against the War quickly grew to more than 30,000 members. This direct involvement in the anti-war movement by American soldiers who had been in Vietnam caused countless Americans to rethink their own positions regarding the war. Attitudes were changing–fast.

Although the Woodstock Concert is best remembered for the music, mud, sex, and drugs, it was, in fact, an anti-war protest rally that drew more than half-a-million people.

The News Media Ended Their Support

Editorials across America began to seriously question government decisions regarding the conduct of the war. The number of newspapers across American opposed to the government's conduct of the war increased monthly.

Life Magazine, a longtime supporter of the war, announced in October 1967 that it would no longer support President Johnson's war policies. "The U. S. is in Vietnam for honorable and sensible purposes. What the U. S. has undertaken there is obviously harder, longer, more complicated than the U. S. Leadership foresaw."

Walter Cronkite, at the time America's most trusted broadcaster, traveled to Vietnam to see for himself what the situation looked like up close. He reported from there several days. After Cronkite returned home, he ended his February 27, 1968, evening news with an "editorial opinion." That news cast became one of the war's memorable television moments. Cronkite said "...for it seems now more certain than ever, that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate." In retrospect most experts consider this week of Cronkite reporting, along with his personal opinion regarding the unwinnability of the conflict, a critical turning point for the war.

The New York Times infuriated Washington's bureaucracy June 13, 1971, when it published excerpts from a classified study that became known as the Pentagon Papers.

This was a top secret study of U. S. involvement in southeast Asia from World War II though May 1968, detailing the government's arrogance, deception, and miscalculations in the handling of matters there. Of course the

report had to include the government's unwillingness to disclose many aspects of America's involvement in questionable pursuits in that part of the world. The 47 volume study contained much that the government did not want the public to know.

The Justice Department obtained, on national security grounds, a court injunction barring further publication of the study. The Supreme Court ruled on June 30 that the constitutional guarantee of a free press overrode any national security considerations and allowed publication to continue.

Soon thereafter the government indicted Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo, charging them with espionage, theft, and conspiracy. A federal court judge dismissed all charges against both men on May 11, 1973, citing "improper government conduct."

The Army Covered up a Mass Killing of Civilians

A search-and-destroy mission went horribly wrong and American soldiers killed hundreds of women and children at a village called My Lai.

The massacre at My Lai took place March 16, 1968, however the U. S. Military successfully covered up the incident until November 1969.

When the horrific images of rows and piles of bodies of women and children filled television screens world wide, the vast majority of Americans were shocked and outraged. A surprising number of politicians and military leaders appeared unable to understand what the fuss was about.

American soldiers of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 10th Infantry, were participating in an airborne assault again suspected Viet Cong in Quang Ngai Province. They entered a hamlet called My Lai, then, angered at finding no enemy soldiers there, the Americans reportedly began indiscriminately killing every civilian inhabitant they encountered.

A helicopter pilot, hovering above to provide air support to the operation, suddenly realized what he was witnessing. He landed his chopper, and began to evacuate civilians to safety.

The unit reportedly filed an initial report stating that they had killed 69 Viet Cong soldiers and making no mention of civilian casualties. A subsequent report indicated that they had killed 128 Viet Cong and that 22 civilians had also died in the action.

Afterwards, when pressed to reveal the actual number of civilians killed at My Lai, the Army reported that they did not try to take a definitive body count. A memorial eventually erected near the site lists 504 names of victims.

The Army successfully concealed the truth about what had happened at My Lai until November 1969, when a Vietnam veteran came forward with sufficient information to force the Army to investigate. Although 26 soldiers were supposed to be brought to trial after the official investigation ended, Lieutenant William Calley became the face most closely related to this tragedy. Calley reportedly was the only soldier convicted in the matter. He was also the only man to serve any prison time as a result of the massacre.

After a court-martial that lasted four months, Calley was convicted on March 29, 1971. Originally he was sentenced to life in prison. Two days later President Nixon order Calley released pending approval of his sentence. The sentence subsequently was reduced and Calley served four and a half months at Fort Benning, Georgia.

The Light at the End of the Tunnel

General William Westmoreland said in a speech at the National Press Club in 1968: "We have reached an important point where the end begins to come into view." He said that he thought the United States was experiencing improved fortunes in 1968, to the extent that we could now start to "see the light at the end of the tunnel."

Without a doubt, the phrase "light at the end of the tunnel," was quoted more than any other. It is remembered as a prime example of a major government promise of something that never came to be.

The "Secret War"

Even though it was called the Vietnam War, the conflict expanded to involve two other former French colonies: Cambodia and Laos.

After the North Vietnamese had established supply routes and logistical bases in Cambodia, the United States began in secret an intensive bombing campaign to disrupt and destroy them. Thus, the war spilled across the borders in 1969.

Americans would learn much later that U.S. war planes had dropped some half-million tons of bombs in Cambodia, killing an estimated 100,000 Cambodian civilians in the process.

At about the same time American forces started secretly operating in Laos. At first they established listening posts and radar stations in Laos but the incursion did not go unnoticed. The Americans soon were under attack and fighting back.

The Nixon administration's revelation the following year that U. S. troops had secretly been operating in Cambodia, infuriated protesters and sparked rallies across America. At one of these protest rallies at Kent State University, May 4, 1970, Ohio National Guardsmen fired on the unarmed students, killing four and wounding several others.

Photographer John Filo was awarded a Pulitzer for his picture of a screaming girl, kneeling beside the body of a student shot by the guard.

America Exits

American troop levels in Vietnam peaked in 1968 at 536,000 men. As troops were brought home without being replaced, the number remaining in Vietnam continued to drop. Some 475,000 remained in 1969; down to 334,000 in 1970, then 156,000 in 1971.

With Nixon's inauguration Congress drastically cut spending for the war, including the amount of aid being given to South Vietnam.

In 1971 Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, in effect removing the authority for operations in southeast Asia.

The Paris Peace Accords, signed in January 1973, were supposed to end the fighting and start the exchange of prisoners. Fighting continued.

Another well remembered image of that era is that of the presentation of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize. It had been awarded jointly to Henry Kissinger of the United States and Le Duc Tho of North Vietnam for the Paris Peace Accords. Le Duc Tho declined the award.

On June 19, 1973, Congress, fed up with the war, passed legislation calling for a halt to all American military action in southeast Asia by August 15.

The Viet Cong took control of more and more territory in the south. On April 23, 1975, they entered Saigon.

Virtually every American who was at least ten years old in 1975 remembers seeing the unforgettable television pictures of helicopters rescuing the last Americans from the U. S. Embassy in Saigon.

At that time it was hailed as the largest evacuation by helicopter ever undertaken.

Sensing that the Americans might be preparing to withdraw, more than 10,000 people had lined up outside the American embassy, attempting to obtain a visa and hoping to be evacuated with the Americans. Some 200 marines were brought from an American ship just off shore to protect the perimeter of the embassy.

The ambassador and the commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet had agreed in advance that the signal to start the evacuation would be the playing of Bing Crosby's White Christmas on the radio. Upon hearing the song, marines inside the embassy compound were to cut down the trees to create more open space for helicopters coming ashore from the ships to land.

The first helicopter landed April 29 at 3:30 a.m. Soon helicopters were landing two-by-two at five minute intervals. They flew to American ships anchored off shore, discharged their passengers, and immediately returned. The process continued for about 28 hours.

An officer ordered the marines still controlling the frenzied crowd outside the embassy walls to come inside and secure the 20-foot-tall embassy doors. Those marines were immediately boarded choppers and were flown to safety.

Sadly two Marines from that group were killed just prior to their comrades being ordered to move inside the compound. Corporal Charles McMahon, age 22, from Woburn, Massachusetts, and Lance Corporal Darwin L. Judge, age 19, from Marshalltown, Iowa, died from artillery fire. They became the last two American service men to die in Vietnam.

An unexpected lull in the evacuation caused concern among the few remaining Americans in the embassy compound. The officer in charge radioed the 7th Fleet to ask what had happened. He must have been amazed to be told that the 7th Fleet thought that everybody had already been evacuated!

North Vietnamese troops had entered Saigon several days earlier and those Americans remaining on the embassy roof could clearly hear Vietnamese tanks approaching the compound.

Three more choppers were immediately dispatched to the embassy's roof, which could only accommodate one helicopter at a time. The first plane landed, men rushed aboard, and the chopper departed. All of the men swiftly boarded the two remaining choppers and the final Americans flew out of Vietnam.

Many Americans watched on their televisions the evacuation being broadcast live. Although some felt disgraced at what they perceived as the war's failure, a greater number felt jubilant because they had witnessed what they knew would be the absolute end of Americans suffering and dying for South Vietnam.

Return to TOP of page!

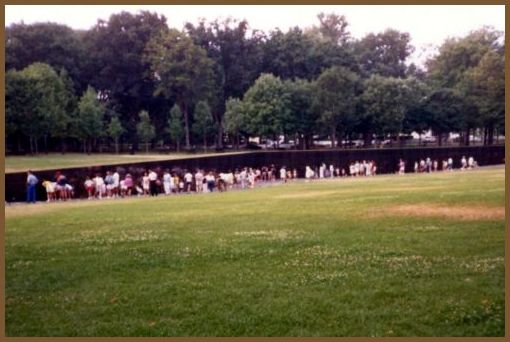

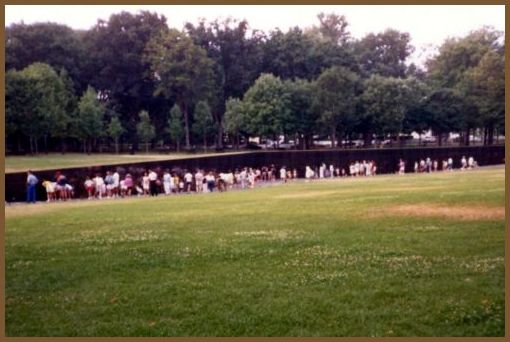

THE VIETNAM MEMORIAL WALL HELPED HEAL AMERICA

© copyright 2010, Herman McDaniel

Maya Ying Lin, was 21 years old, an architectural undergraduate student at Yale University, when she designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial to be built in Washington, D.C.

A non-government organization, The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Inc., had announced plans to build a monument honoring all who had died in that war. Through private contributions from companies, civic groups, foundations, unions, veterans, and ordinary citizens, they raised some $9,000,000 to build the memorial.

The federal government agreed to provide a site on the federal mall on which the memorial would be built.

In October 1980, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund invited U. S. citizens, age 18 or older, to submit designs for the proposed memorial. They set the deadline for submissions as March 31, 1981. The Fund promised that entries would be judged anonymously, giving every entrant the expectation that his or her design would be judged on its merit.

The 1,421 designs submitted in the competition were arranged in rows in a hanger at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, to be judged. Each design was identified only by a number to create a truly "blind" competition.

Eight prominent artists and architects had been appointed to evaluate the designs and determine how well they met the four design criteria: be reflective and contemplative in character; harmonize with its surroundings; contain the names of those who had died in the conflict or were still missing; and make no political statement about the war.

Each juror examined every design. They narrowed the number of entries under consideration from the original 1,421 to 232. Then they winnowed the remaining entries down to 39.

On May 1, 1981, the jury announced that they had selected entry number 1,026, agreeing that it clearly complied with the formal requirements. The jury also said that they thought the open nature of this unusual design would encourage access without barriers at all hours, while shielding visitors from traffic noise.

Lin's design was unconventional for a war memorial. It did not gloat of victories or lionize military leaders. It honored equally the individuals who had died in Vietnam.

Some took exception to the design because it contained neither a flagpole nor statue.

Lin told reporters that the design created an opening or wound in the earth to symbolize the gravity of the loss of so many soldiers.

Some expressed displeasure that the memorial had been designed by an Asian. Miss Linn, of Chinese heritage, was born in Athens, Ohio, in 1959.

Even though Miss Lin had been born in Athens, Ohio, in 1959, some expressed displeasure that the memorial had been designed by an Asian. Miss Lin is Chinese-American.

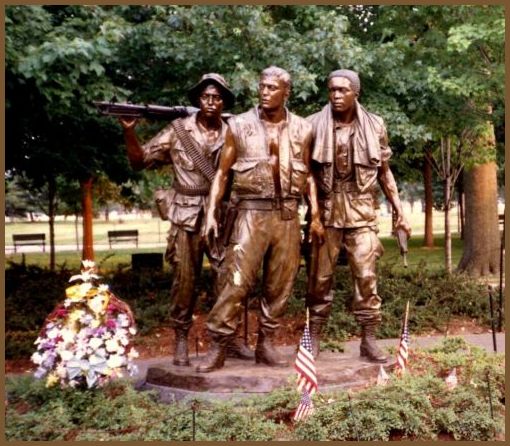

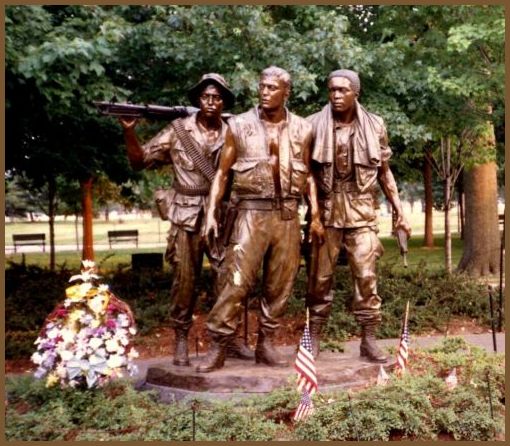

Before Congress the young architectural student successfully defended her position that a flagpole did not fit into her design. They reached a compromise to locate a flagpole nearby but not touching The Wall. They also agreed to add a statue depicting fighting men a short distance from The Wall itself.

Groundbreaking day was March 26, 1982. The Memorial was completed in October and dedicated November 13, 1982.

A life-size sculpture depicting three fighting men and the promised flagpole were

installed near the west end of The Wall in 1984.

It was also in 1984 that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund turned the Memorial over to the United States to be managed and maintained by the National Park Service.

Another sculpture was added in 1993 to commemorate the 67 women (eight military and 59 civilians) who had died in that war.

Design of The Wall

The Wall actually consists of two main sections that meet in the middle at an angle of 125 degrees. The two sections each contain 72 panels and are slightly longer than 246 feet long.

The panels at the apex, are slightly more than 10 feet tall.

One section of The Wall points East, toward the Washington Monument. The other points West, toward the Lincoln Memorial.

Officials chose an extremely hard, black granite that has a very fine grain, because the names carved into the Memorial should remain readable for several centuries. The panels have been polished to a high finish so as to reflect the sky, the environment, and visitors.

The names of officers and enlisted personnel are intermixed, with no ranks carved on The Wall, because all are considered equal in death.

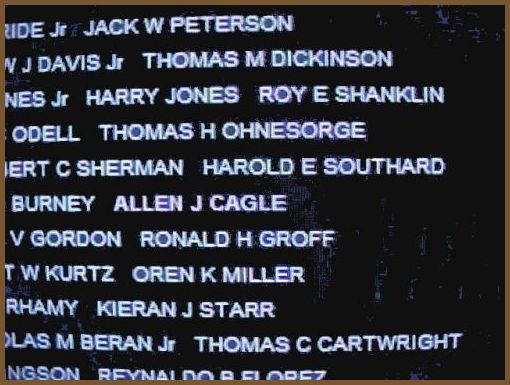

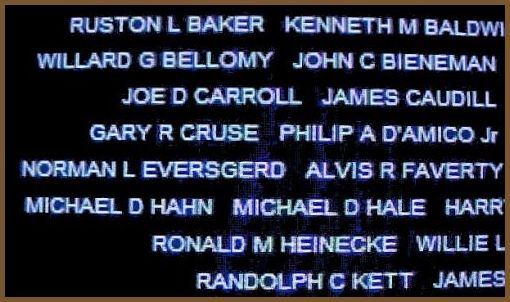

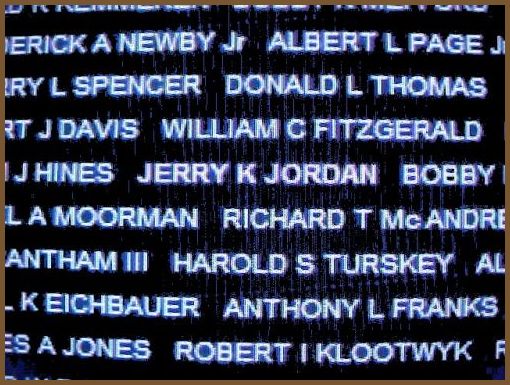

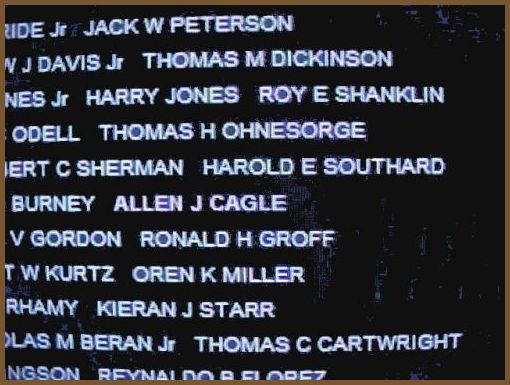

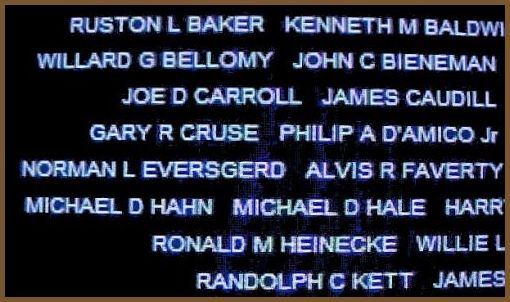

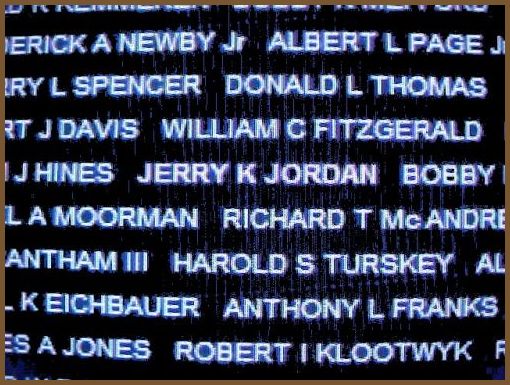

Names on the wall are arranged by date of death, starting in the middle of The Wall, at its highest point. The names of those who died first are on Panel 1 East. The names continue filling panels toward the Washington Monument until Panel 70 East, where some of the names of those who died May 25, 1968, appear.

The names are continued in date of death sequence at Panel 70 West, nearest the Lincoln Memorial, where the remaining names of those who died May 25, 1968, were carved. The names continue to Panel 69 West, 68 West, etc. The names of the last to die appear on Panel 1 West, adjacent the names of the first to die, on Panel 1 East. This arrangement creates an unbroken circle that has been described as "a wound that is closed and healing."

Even though the names are arranged in date of death sequence, no dates separate the groupings on the panels. Names of all who died on the same date are arranged alphabetically within that grouping.

The names originally were carved with five on each line. Some lines now contain six names, with one probably out of alphabetical sequence, because it has been added at the end of an existing line.

To locate a person's name on The Wall, visitors must find on which panel and line number the name was carved. If someone wants to find the names of the four Murray soldiers on T

he Wall, here are the details needed:

Allen James Cagle can be found on Panel 22E, line 80.

Raymond Beam is on Panel 44W, line 47.

Gary Robert Cruse is listed on Panel 48W, line 40.

Jerry Kenneth Jordan is listed on Panel 24E, line 87.

Since each panel is numbered at the bottom, and all East panels are in the section nearest the Washington Monument, and all West panels are in the opposite section, nearest the Lincoln Memorial, finding the correct panel is a breeze. From the top of the appropriate panel, count the number of lines indicated. To make it easier to count lines, some 1170 dots have been carved into the even-numbered panels. Starting at the top of the panel dots are visible at every tenth line, enabling visitors to count by ten when searching for a line carved far from the top of a panel. The name will be on that line.

Symbols have been used beside each name to convey specific information. A diamond means "killed, body recovered." Because it would easy to change without mutilating the memorial, a plus sign was used to indicate "missing in action." A symbol was even set aside to

use in case a person originally listed as missing in action should return alive; a circle would be carved around the plus sign to reflect the changed status. None of those originally listed as MIA ever returned alive.

When remains are found and positively identified as a soldier originally listed as missing in action, a diamond is carved on top of the plus sign. With the passing of decades the plus sign has come to mean "killed, body not recovered."

On the West Panels the symbols precede the names. On the East panels the symbols follow the names.

Those Who Died

More than half of those who died in Vietnam were age 21 or younger. To be more precise, half died when aged 21 years and 4 months or younger.

Some 14,095 died at age 20, more than the dead of any other age.

Fourteen soldiers died before their 18th birthday.

The names of 67 women are on The Wall, some were military personnel, others were civilians in the war zone supporting the troops.

The greatest number of deaths occurred in 1968, when 16,589 died. The second deadliest year was 1969, when 11, 614 died, followed by 1967, when 11,153 died.

The Defense Department, in a report last updated March, 1997, reported that the names of 50,112 White soldiers are listed on The Wall; Blacks totaled 7,264; Asians 115; American Indians 226; and Others totaled 467. Since 1997 eighty-eight names have been added to The Wall, six of them in 2010.

DOD reported that 17,672 of the dead had been drafted into service.

Soldiers of every grade or rank are listed on The Wall. The number of officers listed is 7,878. Enlisted personnel total 50,306. The total at that time stood at 58,178. Names have been added since that date.

The ranks of First Lieutenant and Captain (and equivalents) had the greatest number of officer deaths. Among the enlisted the rank of E-3 (Private First Class) counted 17,995 dead while E-4 (Corporal and equivalent) suffered 14,715 deaths.

By service the breakdown of the dead based on the 1997 statistics were: Army 38,196; Marine Corps 14,837; USAF 2,583; Navy 2,555; and Coast Guard 7.

The Youngest Soldier on The Wall

PFC. James Calvin Ward from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Casualty #1,282, appears to be the youngest American soldier on The Wall. He served with the 1st Cavalry Division. Army records indicate that he was born January 26, 1948, and killed by small arms fire in Binh Dinh Province October 11, 1965. That means he was actually less than 17 years and 10 months old, therefore his age would be listed as 17 when he was killed.

Two other soldiers initially appeared to have been younger than Wade but their death dates had been recorded incorrectly, probably a keying error.

One dozen service men listed on The Wall died prior to their 18th birthday.

The Oldest Killed in Vietnam

Major-General Bruno Arthur Hochmuth was the oldest soldier killed in the war. He was Commanding General of the 3rd Marine Division. He and four other men were killed when their helicopter exploded in Thus Thien Province.

Military records list his date of birth as May 10, 1911, and his date of death as November 14, 1967, making him 56 years old when he died. He was designated as casualty number 18,016.

Much information about General Hochmuth is available on the internet. Marine Sergeant Greg Cordova posted a story telling about an experience he had involving the general while he was in boot-camp. Cordova had been assigned to clean the general's office. He swept, dusted, polished. On a whim he took the general's cap from his desk and put it on. As he was admiring himself as pretend General Cordova in a mirror, the real General Hochmuth unexpectedly returned to his office.

Caught red-handed Cordova had visions of his Marine Corps dreams being flushed down a toilet.

Instead, General Hochmuth smiled and told Cordova, "it looks better on you than it does on me." Almost immediately he added, "Carry on, Marine, you did a good job here."

Several similar stories have been posted, all documenting that this particular General was a man who could relate well to fellow soldiers of all ranks.

Although 15 soldiers appear to have been older than General Hochmuth when they died, some of their dates of death were skewed by the military initially listing them as missing in action, then years later officially declaring them dead. Such assigned death dates greatly exaggerated their life spans. Others died of natural causes such as stroke or heart attack. General Hochmuth clearly was the oldest American soldier killed in the war.

He also holds the distinction of being the only Marine Corps General to die in Vietnam.

Names on the Wall

Only one state has fewer than 100 names on The Wall, Alaska with 57.

Seven states have more than 2,500 each: California 5,572; New York 4,120; Texas 3,415; Pennsylvania 3,142; Ohio 3,095; Illinois 2,933; and Michigan 2,654.

Georgia has 1,582 names on The Wall. These include 1,134 who served in the Army; 341 Marines; 58 Airmen; and 49 Sailors.

Reaction of Visitors

Visitors coming specifically to find names of friends on The Wall have a very different reaction than those who stop by merely to see the Memorial. The latter, especially if younger, fail to realize the sanctity of the place and continue their tourist-in-a-hurry chatter while they rush along the Memorial, laughing and cavorting as they snap an occasional picture, eager to be on the way to their next scheduled stop.

Those seeking names tend to be more somber, respectful, and sorrowful. These appear to experience a far more personal connection. They tend to reach out and touch the names of people they knew. Some quietly hold private conversations with the deceased. In facing the panel where a loved one's name appears, a visitor sees his or her own reflection mirrored by the highly polished granite. This gives them a feeling that they have connected with someone long gone.

Thousands of visitors each month leave mementoes, flowers, photos, trinkets, military medals, and so forth, below a panel bearing the name of someone they knew.

It is not unusual to see visibly aged Vietnam Veterans come to the wall, sometimes in pairs or small groups, to visit former comrades. After emotional visits, often with tears, these hardened veterans do something they probably never did when they were young, but have wished many times that they had done with their fallen comrade. They embrace each other. They hug tightly their military buddies remaining alive. It's even become acceptable in 2010 for one veteran to quietly tell another, "I love you, man."

Return to TOP of page!

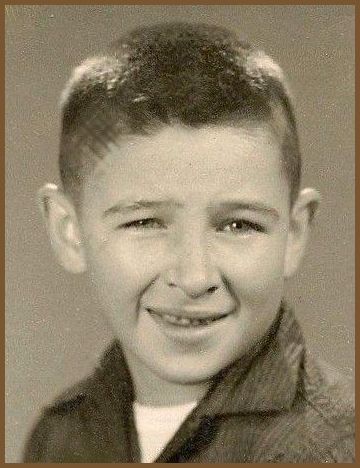

JIMMY CAGLE BECOMES MURRAY'S FIRST SOLDIER TO DIE IN VIETNAM

© Copyright 2010, Herman McDaniel

To many, it must have seemed more like a very sad, patriotic movie than the very tragically sad and disturbing event that it actually was. A neighbor boy had been killed in far off Vietnam, his body had arrived home in a sealed, flag-draped coffin, and he was being buried with all of the tradition and ceremony of a military funeral in Dawnville Cemetery–on the Fourth of July, no less. Sadly, this was the real-life story of Jimmy Cagle, who lived his too-short life in Murray County, Georgia.

Jimmy, the first soldier from Murray killed in Vietnam, died Sunday, June 25, 1967.

Background

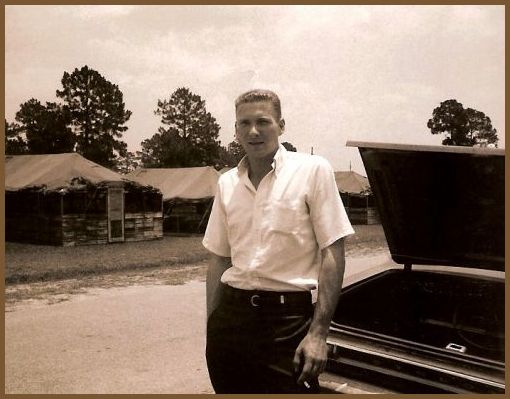

Cagles were plentiful in Murray County in the 1920s. The Census for 1930 listed Jackson and Emma Cagle, living in Coosawattee, Murray County. They were grandparents of Jimmy Cagle. It was their son, listed as A. J., then age 9, who would eventually become the father of Allen James Cagle, Jr., who died in Vietnam.

That Census listed five other Cagle families on the same page as the family of Jackson and Emma, meaning they all lived nearby. The Census indicated that every member of those six Cagle families had been born in Georgia. Apparently the Cagles had been settled in Georgia for decades.

A. J., born about 1921, eventually married, fathered two boys, Jimmy and Ronnie, before he was killed in World War II.

A. J.'s widow (Jimmy and Ronald's mother) remarried. When she moved to Los Angeles, California, the boys stayed in Murray to live with their maternal grandparents, Coy and Lucille Lotspeich, near Fuller's Chapel, some twelve miles north of Chatsworth.

Because the youngsters lived with their grandparents, they had a much closer than usual relationship with them seeming more like parents and sons. A similar situation existed with an uncle, Joseph Coy Lotspeich, who still was living at home. After they became adults all three agreed that they were more like 3 brothers than an uncle and two nephews.

Like most rural families living in Murray at that time, the Lotspeichs farmed. So Jimmy grew up doing the usual things that boys living on farms did in those days. From a very early age he served as a farm laborer, worked in the fields, took care of animals, cleaned barn stalls, worked a garden, etc.

Jimmy and Ronnie knew that their dad had died in the war and often asked their granddad whether they would have to go away to fight in a war. All he could tell them was that he hoped that they would not.

Friends and family described Jimmy in various ways: "shy," "very nice," and "not very outspoken." Apparently, compared to others his age, he was a boy of few words. He seemed to prefer his own company over that of other boys his age.

Jimmy disliked the whole idea of school. As soon as he could do so, he dropped out and found himself a job.

At age 20, Jimmy married Jane Young, whose parents, J. B. and Juanita Young lived at Spring Place. Because they knew that Jimmy would be drafted very soon, the young couple lived with Jane's parents.

At the time that he was drafted Jimmy had been working at Sane's Body Shop in Dalton.

Answering the Draft Summons

When boys reached draft age the Vietnam War required that virtually every young man serve a tour of duty. Although Jimmy was older than Ronnie, the draft board called Ronnie to duty first, because single men were drafted before those who were married. Ronnie was not destined to serve in Vietnam. Jimmy was destined to serve there–and to die there.

Ronnie told friends and family that Jimmy had always said that, even if the draft board sent him a notice, he would not serve. When the postman delivered his draft notice, October 26, 1966, Jimmy had come to realize that he really had no choice other than to answer the call to serve.

After he completed basic training, followed by Infantry training, Jimmy received orders for Vietnam.

While home on leave prior to deployment in April 1967, Jimmy confided to several people closest to him that he feared, more than anything else, the possibility of being in a military vehicle that hit a land-mine. Several of his letters written from Vietnam to his family echoed that fear.

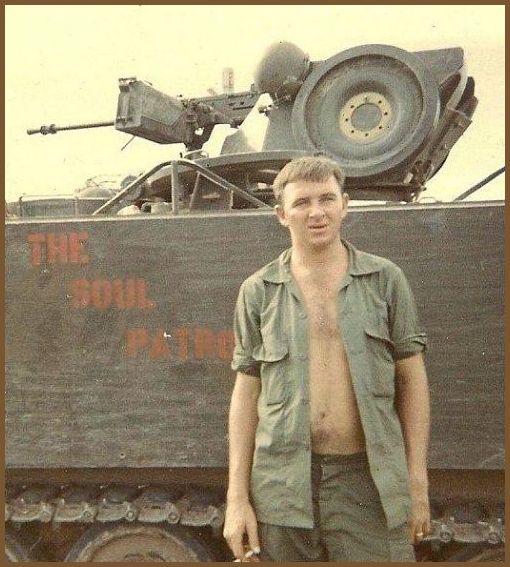

Jimmy Cagle's worst fear became a reality on June 25, 1967, in Binh Duong Province. The Army records indicate that while he was riding in an armored personnel carrier, the vehicle ran over a mine and he "died outright from multiple fragmentation wounds."

Across Vietnam 22 Americans died that day. The Defense Department designated Allen James Cagle Casualty Number 13,894. They assigned casualty numbers in the order, by date and time, that each soldier died. From DOD's reckoning, Jimmy Cagle was the 13,894th soldier to die in Vietnam.

One other soldier from Jimmy's unit, Company B, 4th Battalion, 23nd Infantry (Mechanized), died that day. Sergeant Wayne Victor Gordon, age 20, from Detroit, Michigan, also "died outright from multiple fragmentation wounds." The records are unclear whether the two died in the same incident.

Three other men died in the same province that day, possibly in the same fighting. They were: Major Robert Warner Kurtz, age 32, from Culver, Indiana; Captain Alfred Walker Murphy, age 24, from San Antonio, Texas; and Sergeant Wayne Victor Gordon, age 20, from Detroit, Michigan.

Across the total span of the Vietnam war, more Private First Class soldiers died than any other rank. Some 12,822 are counted among the dead.

Soldiers grade E-4 (Corporal or Specialist Four) accounted for the second greatest number of deaths. The total count of E-4s dead was 11,528.

The war had clearly escalated by 1967. The Department of Defense Manpower Data Center reported that there were more than 485,000 Americans serving in Vietnam that year.

American soldiers who died in Vietnam that year totaled 6,467–more than the total for all who had died there in the preceding years combined.

Jimmy Comes Home

An article in the Atlanta Constitution quoted Murray County Sheriff Judy Poag's account of informing the Lotspeichs of their grandson's death: "When I got out there, he (Coy Lotspeich) was at a neighbor's house. I went to get him and bring him back home to tell him about Jimmy. But when he saw me drive up, he said, ‘Judy, you bring sad news, don't you?'"

"I said ‘yes.'"

"He said ‘Jimmy's dead. He got hit by a mine. You don't have to tell me anything, Sheriff.'"

"I didn't say another word."

Jimmy Cagle was buried with full military honors in Dawnville Cemetery, Whitfield County, Georgia.

A few weeks later, in a private ceremony in the home of Jimmy's widow and inlaws, the Army awarded Jimmy the Purple Heart posthumously. His authorized medals already included The National Defense Service Medal, The Vietnam Service Medal, and The Vietnam Campaign Medal.

By an odd coincidence, the Dalton Citizen article about Jimmy being awarded the Purple Heart appeared back-to-back with an article reporting that Murray's second soldier, Jerry Kenneth Jordan, had been killed in Vietnam on August 10, 1967. The two deaths, occurring so close together, quickly brought the far-off war home to the people of Murray County.

Correcting a Newspaper Error

The Atlanta Constitution article reporting Pfc. Cagle's death, mentioned above, erroneously reported that Cagle's father had been the first Murray County soldier to die in World War II. This clearly was in error because the older Cagle was killed in fighting in France in March 1944.

The first Murray soldier killed in World War II actually was Huse B. Terry. The Chatsworth Times, in the issue dated March 26, 1942, reported Terry's death, headlining it as "Murray's First War Casualty." Terry was serving in the Navy when the cruiser Pillsbury sank; all on board died.

The last time the elder Cagle came home on leave, his son, Allen James Cagle, Jr., was about 8 months old. The father never saw his second son, Ronald, who was born while his father was fighting in France. The boys' father initially was reported as missing in action. Six months later authorities notified the family that he had been killed in action near the Rhine River. After the war the Army returned his body to America and his family buried him in Murray's New Prospect Cemetery.

The Lotspeichs buried their grandson, Jimmy Cagle, in Whitfield County's Dawnville Cemetery.

On the Vietnam Memorial Wall Jimmy Cagle's name is at Panel 22E, line 60.

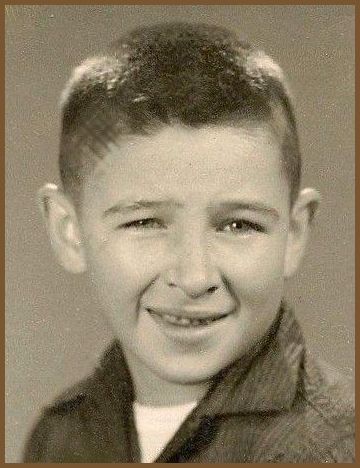

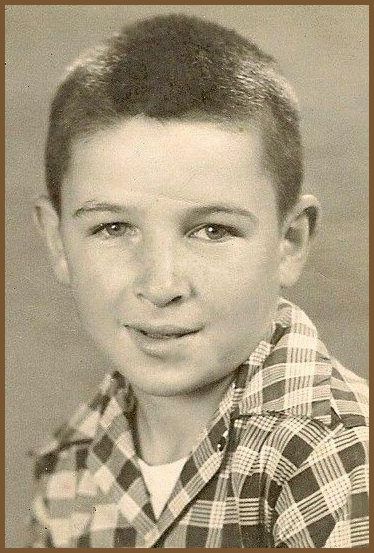

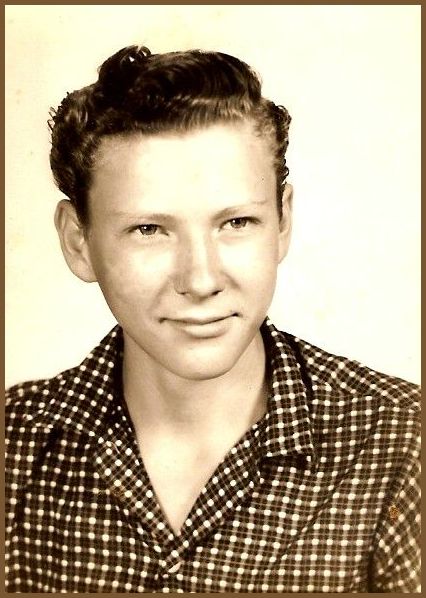

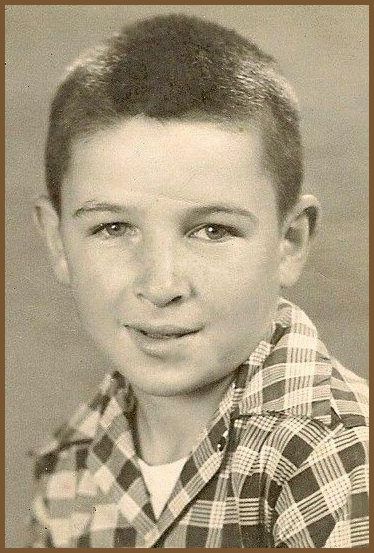

The first two pictures below are Jimmy's school pictures. There's also one of him wearing fatigues. Last is his grave marker.

Return to TOP of page!

JERRY JORDAN BECOMES SECOND MURRAY SOLDIER TO DIE IN VIETNAM

© copyright 2010 Herman McDaniel

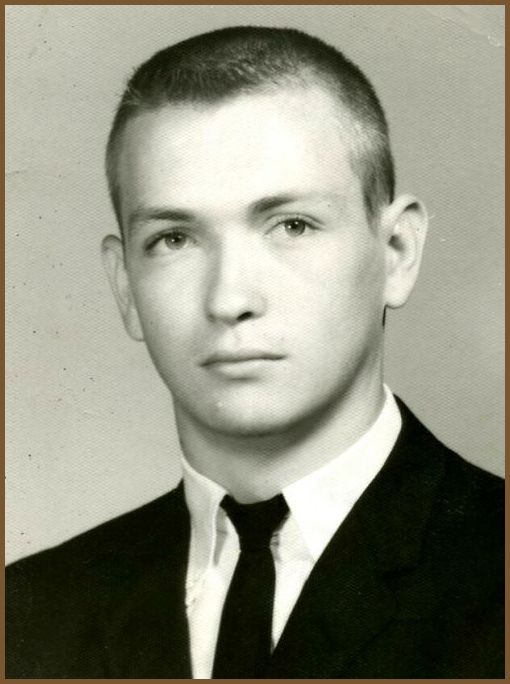

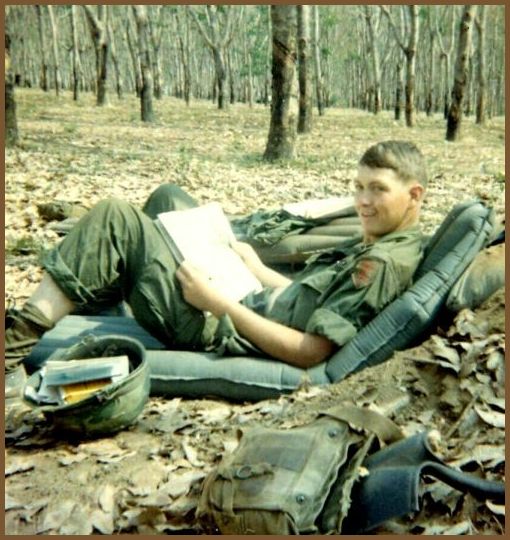

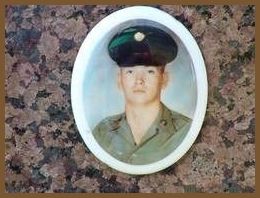

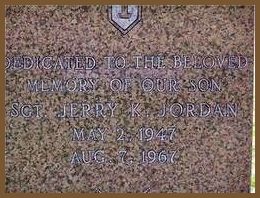

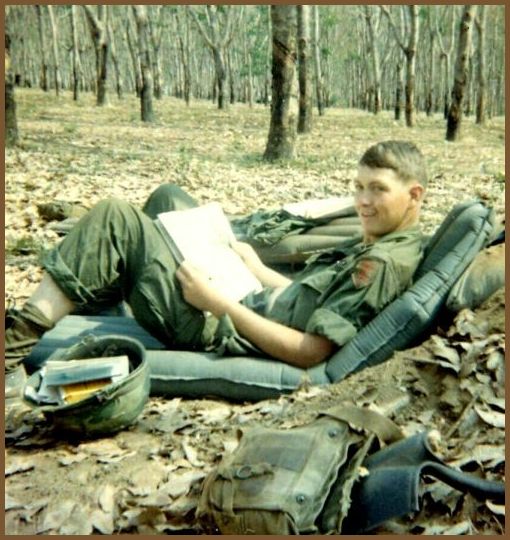

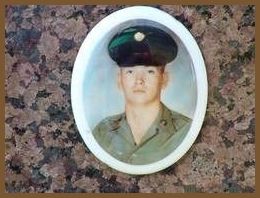

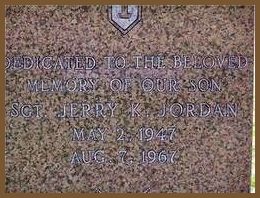

Jerry Kenneth Jordan, the second man from Murray County to be killed in Vietnam, died from enemy fire in Binh Long Province, August 7, 1967. Jerry was a member of Company A, 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division. Although he was only 20 years old when he died, he had attained the rank of Sergeant.

Three other men from Jerry's company died the same day: Sergeant William Joseph Hines, age 22, was from New York City; Sergeant Richard T. McAndrew, Jr., age 21, had lived in Braintree, Massachusetts; Sergeant Samuel Porter, Jr., age 20, hailed from Portsmouth, Virginia; and Specialist Four David L. Scott, 20 years old, from Edwardsburg, Michigan.

One other soldier from the same battalion also was killed that day: Pfc. Van Vernon Trantham, III, age 23, from McComb, Mississippi, was in Company B. He appears to have died in the same incident as Jerry Jordan.

Across Vietnam, 21 American soldiers died that day. That was considered a low death day for 1967. In that tragic year 6,467 Americans died in Vietnam.

Jerry Jordan was one of more than 6,400 American Sergeants to die in Vietnam.

Sergeant Jordan was killed on August 7 and the Army notified his family the very next day, August 8, 1967, a day the family traditionally celebrated two birthdays: Jerry's mother and his brother, Winston.

In his brief life Jerry had earned a bronze star and a purple heart. His service in Vietnam also authorized three other medals: The National Defense Service Medal; The Vietnam Service Medal; and The Vietnam Campaign Medal.

Jerry's brother, Troy, reports that Jerry was so young when he died that he was still growing! Troy said that Jerry had added two inches in the last year of his life, making him nearly 6' 5" tall.

Murray County's farewell to Jerry Kenneth Jordan included his funeral at Casey Springs United Methodist Church and his burial with full military honors in the adjacent church cemetery.

Jerry Jordan's Family Life

Jerry Kenneth Jordan was born May 2, 1947, the second of eight children born to J. T. Jordan and Rachel A. Dalton. J. T. had been born in Murray County in 1924. Rachel was born one year later. The family lived at Coosawattee. Jerry's mother and father were both buried in Casey Springs Cemetery.

Jerry's paternal grandparents were Pardue L. Jordan and Jennie Long. Pardue was born in Texas in 1898 and died in Whitfield County, Georgia in 1956. Jennie was born in Georgia in 1896 and died in 1977 in Gordon County, Georgia.

Jerry's parents, J. T. and Rachel, had 8 children (in birth order): James, Jerry, Winston, Troy, Joyce, Kathryn, Terresa, and Melissa.

His sister, Kathryn, remembers how differently families ate back then. She said that her mother started each day by making 75 biscuits. Then she cooked whatever she happened to have on hand in sufficient quantity to feed her family. Fried eggs were a staple; Jerry alone could devour a half-dozen. Some days the family had home-made sausage, others fried chicken, and immediately after hog-killing, they had tenderloin. Salt-cured streaked meat, sliced and fried, was frequently on the table because it would keep for a long time without refrigeration. It was not unusual to have fried rabbit for breakfast. Whatever the meat, they nearly always had gravy to go with it. One of Kathryn's favorite breakfast foods was chocolate gravy with buttered biscuits. Of course, jams, jellies, honey, sorghum and preserves were part of every breakfast.

The Jordan children attended Southwest Elementary School and Casey Springs United Methodist Church.

Jerry Jordan had lots of friends but his close circle of very special ones included Larry Walraven, Roy McBrayer, Bradley Scott, Minton Young, Doug and Glenn Galman. Two of his brothers, Winston and Troy were usually included in the mix.

At Murray County High School, Jerry especially liked G. I. Maddox and M. D. Jackson. He thought that Rob Leonard made all of the math subjects interesting and challenging. Jerry and Larry Walraven enrolled in Mrs. Nell Ruth Loughridge's Home Economics Class; Jerry told his sister that Mrs. Loughridge was a "terrific teacher," and that he valued greatly what he had learned in her class.

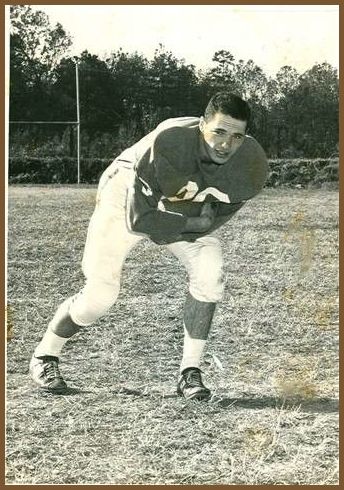

Like many farm boys of that time, Jerry learned to play a guitar so he could participate in G. I. Maddox's String Band. Jerry graduated from Murray County High School in 1966.

The MCHS annual for the graduating class of 1969 included a page In Memory of the four Murray boys who had died in Vietnam: Jerry Jordan, Jimmy Cagle, Gary Cruse, and Raymond Beam.

At MCHS Jerry gained a reputation of being a boy with more than his share of common sense because he had the ability to assess a situation and quickly determine how he should deal with it. These traits played an important role in an incident that occurred when Jerry was about 15 years old.

Jerry, his brothers Winston and Troy, were at their favorite swimming place they called "the sand hole" in Holly Creek. The brothers swam across the creek to sit on a partially submerged tree that had lodged near the far bank. Several neighbor boys had also come to the creek that afternoon. Troy remembers distinctly that some of them could barely swim and he assumed that they were just beginning to learn. One of the younger boys, perhaps eleven or twelve years old, attempted to cross the deepest part of the creek, perhaps nine feet deep, and suddenly was in over his head, bobbing up and down in the water, in serious danger of drowning.

Jerry knew that the younger boy outweighed him and thought that in the boy's panic he probably would pull anyone attempting to rescue him under the water and both would drown. Even so, Jerry knew that he had to attempt to rescue the boy and very quickly. He dove deep into the water and came up slightly behind and under the struggling boy, butting him, pushing him towards the shore. The boy's head rose above water long enough for him to catch a breath. Jerry repeated this maneuver several times until the boy was in water sufficiently shallow for his feet to touch bottom. Jerry and some of the others then took hold of the boy's arms and pulled him on to the creek bank, where they helped him get enough water out of his lungs to allow him to breath again. Everyone present realized that Jerry's quick thinking and decisive action clearly had saved a life.

When the boy who had come so dangerously close to drowning was sufficiently recovered that he wanted to go home, he told those present that he did not want his family to know about his near-drowning. The others agreed that this incident should not become common knowledge in the community and all promised to keep it secret.

Jerry, Winston, and Troy liked spending time together. Troy remembers that many of the things they enjoyed were things boys a few generations before them would have done. For example, the boys hunted together. Their land joined some 10,000 acres owned by the Hiwassee

Land Company. The boys roamed over many miles of this, sharing it only with whatever family happened to have a moonshine still hidden in that vast acreage at any given time. Troy recalls "we never bothered them or their still and they never interfered with our hunting."

Deer had been hunted to extinction, probably by 1920, so the Hiwassee tract had only small game to hunt. Rabbits, squirrels, and quail were plentiful and the Jordan boys brought these home without fail. The family-owned beagles were rated among the best hunting dogs in the county. Even though their dad had restricted the young boys hunting weapons to single barrel shotguns, they all had become good shots and often brought home enough game for the entire family from a few hours of hunting. Jerry could fire his shotgun, reload, then fire it again in about two seconds.

Troy remembers that they ventured into the woods carrying no water or food. They drank water from the streams and they cleaned and roasted over a campfire some of the small game they killed. Everybody seemed to prefer roasted rabbit.

The boys frequently also brought home sufficient fish or frog legs for a family meal. Troy remembers that Jerry "ate like a horse" and could eat an entire pan full of fried rabbit any time it was set before him.

Kathryn Jordan McBrayer remembers how the sisters begged Jerry to take them hunting. She remembers how surprised they were when he unexpectedly relented and agreed to take them,

if they would agree to keep quiet and stay slightly behind him as they moved through the woods. He explained to the puzzled girls that this positioning would permit him to fire safely at any game they encountered. Kathryn smiled when she shared the fact that Jerry had secretly made for each of his sisters a toy wooden rifle to carry on the hunt.

Another incident Kathryn loves to share: their mother was talking on the telephone to someone important. Jerry, wanting to distract her, lit up a corncob pipe filled with tobacco, and blew smoke at his mother. Without interrupting the telephone conversation she tried to shoo him away, but he kept puffing on the pipe and blowing the smoke in her face. His mother was able to smile occasionally at his antic while she continued her business conversation rather smoothly. Jerry, unaccustomed to smoking, suddenly turned green and ran from the house to throw up outside.

Kathryn said that her family knew the families of Raymond Beam and Gary Cruse before the boys were killed. She said that their shared grief subsequently drew all four of the victims' families together in a special bond.

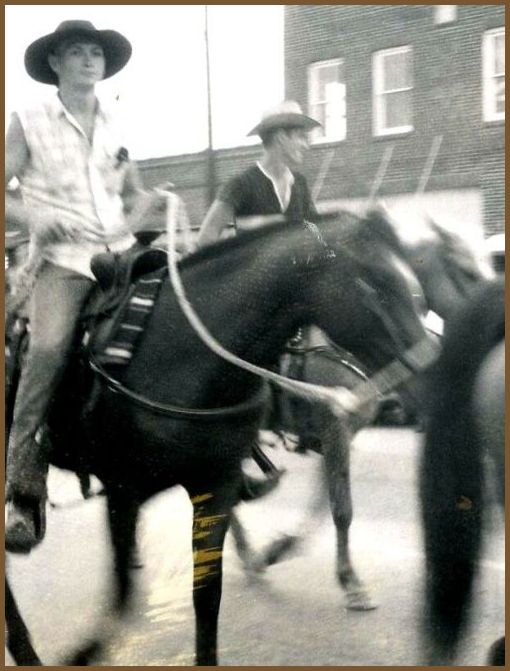

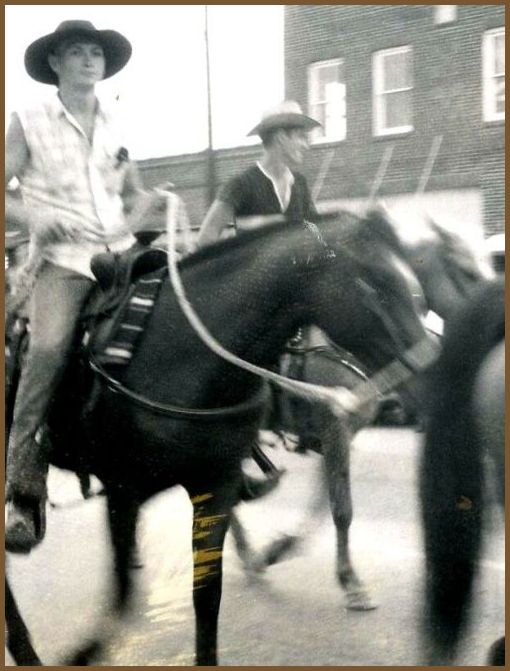

Even though it was the 1960s, the Jordan boys all owned horses and liked to ride. When they decided they wanted to "go to town," they rode the 12 miles to Chatsworth, did what they wanted to do, and rode home, usually by early afternoon. Troy said that they rode on trails rather than roads for nearly the entire distance, having to ride on roadways only a quarter-mile to get from one trail to another.

Jerry took basic training in Kentucky and Jungle training in Louisiana. Afterwards he got the usual leave prior to being deployed to Vietnam.

When Jerry left for Vietnam he sold his horse, Mingo, considered by his siblings as his more highly prized possession. On his way to Vietnam he reconsidered his sale and asked his brother to try to buy Mingo back. The person who had bought the horse sold it back to Jerry for what he had paid for it. Because of the horse's ties to Jerry, Mingo had a loving home with the Jordan family until he died in the early 1990s.

Jerry Kenneth Jordan's name is positioned on the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington at Panel 24E, line 87.

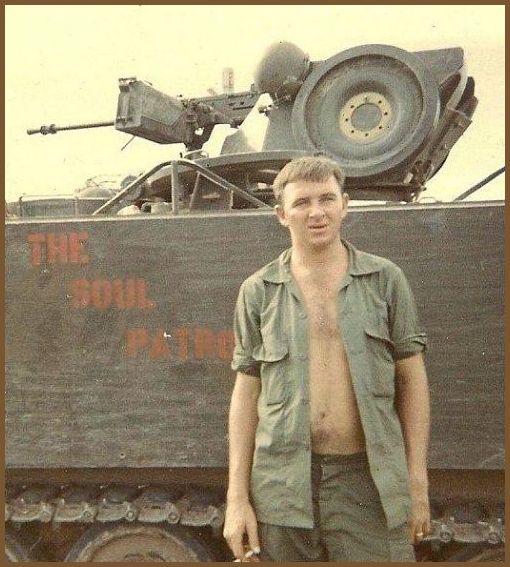

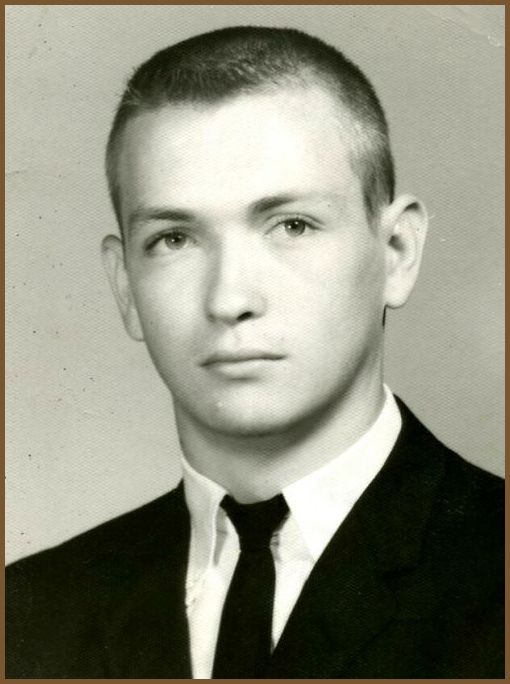

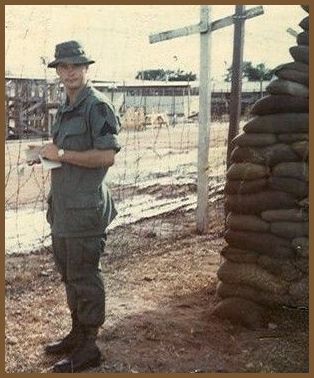

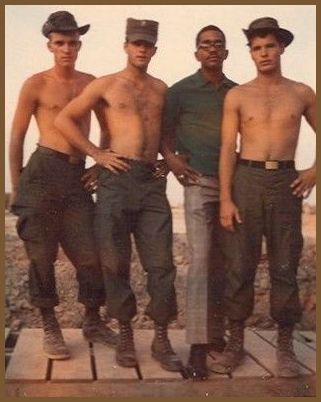

Pictures include Jerry riding "Mingo," Jerry's last Christmas (1966) with his family, his senior picture at Murray County High School, Jerry relaxing in ‘nam, and three of his tombstone.

Return to TOP of page!

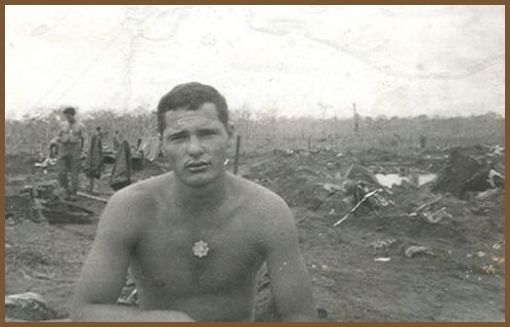

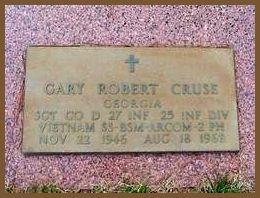

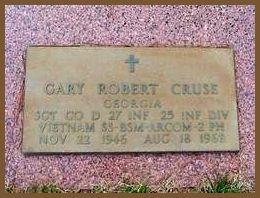

GARY ROBERT CRUSE BECOMES THIRD MURRAY SOLDIER TO DIE IN VIETNAM

© copyright 2010 Herman McDaniel

Sergeant Gary Robert Cruse died in Vietnam, August 18, 1968, the third man from Murray County to be killed there. Department of Defense records reveal that 76 other American service members died in Vietnam on the same day.

The war had escalated, and the number of soldiers serving in Vietnam was near its peak for the entire war. More than 1200 American service men died there in the single month of August, 1968. The official American death toll for that year was 16,589, an average of 45 deaths per day!

American troops in Vietnam in 1968 numbered slightly more than 536,000–the highest number for any year of that war. Fighting along with the Americans that year were 820,000 South Vietnamese, 7,660 Australians, 50,000 South Koreans, 520 New Zealanders, 1,580 Filipinos, and 6,000 Thai troops.

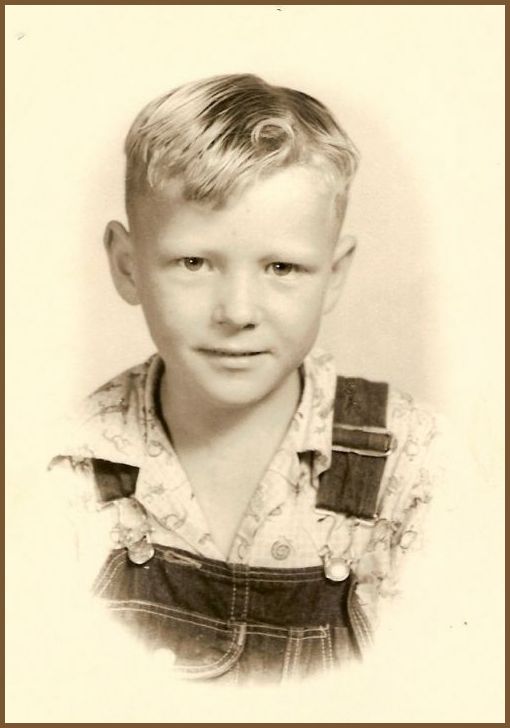

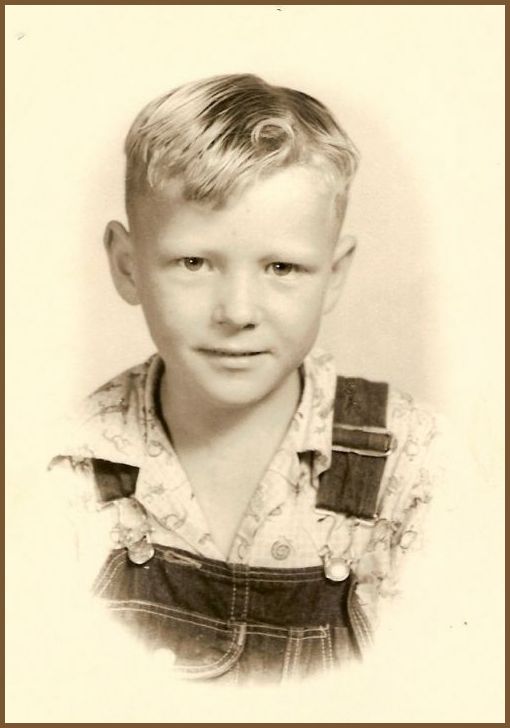

His Early Life

Gary Robert Cruse was born November 22, 1946. His parents were Robert and Maebell (Young) Cruse who lived in the New Hope Community, a part of the Bull Pen district of Murray County. The family also included sisters Trena and Kathy and a brother, Doug.

Gary's paternal grandparents were Milous and Ida Cruse. His maternal grandparents were Kirby and Lucy Young, who also lived in Bull Pen.

Gary's grandfather Young was a preacher. Although Gary was a member of Maranatha Baptist Church, he often attended services wherever his grandfather was pastor at the time.

Gary's family lived in the country so they had the usual horses, cows, hogs, chickens, dogs, etc. During Gary's lifetime the family no longer farmed on a large scale; they did raise a large garden each year and Gary did his share of the work to make that a success. Of course, he knew that the garden would help them to eat well year-round, and Gary definitely looked forward to that–especially when his mom made a peach cobbler for dessert.

Friends and family remember that Gary loved virtually anything having to do with the outdoors. He considered himself lucky to have grown up living in the country.

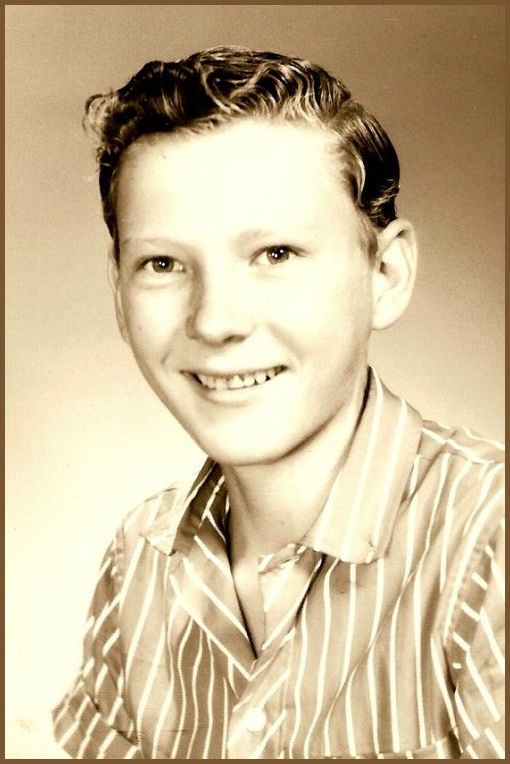

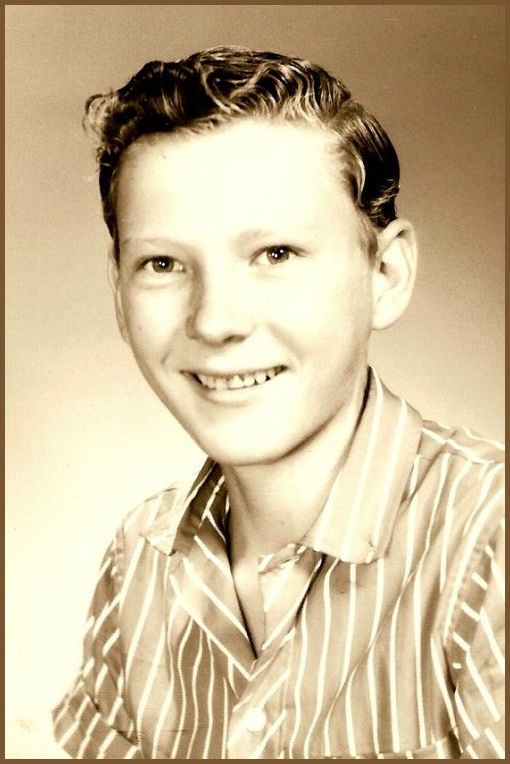

Gary attended Spring Place Grammar School and thought highly of his principal there, Mr. Carl Davis. His mother recalls that Gary was a typical student, respectful but sometimes a bit mischievous, who had no real problems at school. He made friends easily, earned the respect of his classmates, and demonstrated leadership qualities at an early age.

When Gary entered Murray County High School, his greatest short-term aspiration was to honorably do his military stint, and return intact to Murray County. He could then decide what he wanted to do with the remainder of his life. Like most high school students of that time, Gary knew that the war made any other approach unrealistic. The draft had been reinstated as a means of guaranteeing that the military would have all of the soldiers needed for what seemed an ever-expanding war in southeast Asia. Unless a boy had a college student deferment or was in bad physical condition, he could count on being summoned to serve.

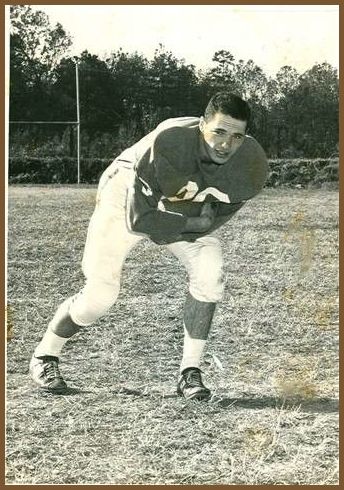

Gary applied himself and quickly demonstrated at MCHS that he could gain the respect and cooperation of fellow students from the entire county, especially on the football field. He responded well to coaching and developed into a very competent team player.

Kensel Headrick, a team-mate remembers Gary as "the fastest guy in 7AA Region, with an attitude that made it apparent that he wanted to win at all costs. Although he had a backbone of steel and was not afraid of anybody on the field, he would never intentionally hurt another player."

Gary counted among his very closest friends, Kensel Headrick, Ted Townsend, and Johnny Waters. He also considered his football coaches, Doug Griffin and Frank Ross his friends.

One of the lesser known aspects of Gary's young life was that he had aspirations to someday race stock cars. His uncle owned North Georgia Speedway and somehow Gary just happened to have had a key. On several occasions he and his buddy, Kensel Headrick, went there late at night and took a few turns around the track in Gary's ‘59 Ford.

Johnny Waters recalls that his family moved to Murray in January 1966, midway through his junior year. The 16 year-old knew no one at school but somehow one of the most popular jocks on campus quickly became Johnny's closest buddy. The two spent time together running track, practicing football, playing football, working at Fort Mountain State Park, and just riding around Murray's back roads. Some 18 months later they both graduated with the class of 1967.

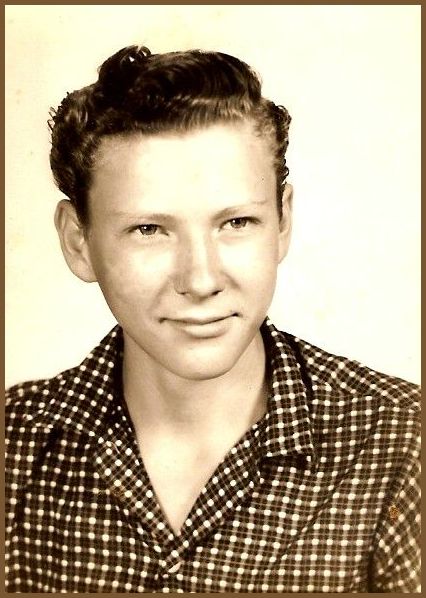

Gary Becomes a Soldier

Gary received his draft summons immediately after graduation. He took basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, followed by advanced infantry training at Fort McClellan, Alabama.

After completing his training, Gary came home on leave, with orders to deploy to Vietnam upon completion of his leave. He confided to his mother that, because he knew that the lives of his fellow soldiers would be at stake, he had worked much harder trying to become a good soldier than he had ever worked in his quest to excel in football at Murray High.

Gary's mother also remembers him telling her that he had to go to Vietnam because he felt certain that if America did not deal with the present threat there, the enemy would eventually come to America.

Johnny Waters recalls with deep sadness driving Gary to the Atlanta Airport to board a flight to San Francisco, enroute to Vietnam. "I parked the car, got out, and got his duffel bag from the trunk, planning to walk with him into the airport. I was surprised and a bit disappointed when Gary told me that he hated goodbyes and wanted to walk into the terminal alone. We shook hands, he entered the terminal, and I drove home, knowing that I might not ever see Gary alive again."

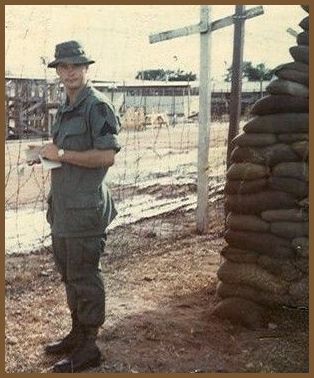

After Gary arrived in the war zone in November 1967, he wrote home virtually every day. He knew that his family would worry and he wanted to lessen their fears by constantly reminding them with his letters that he was still okay.

Gary wrote to his parents, July 20, 1968: "I'm doing just fine. Today finished my 8th month. Tomorrow I start my 9th month. I should be getting off this line toward the end of it."

Soldiers "on the line" were combing the country, roughing it, constantly facing unexpected contact with enemy soldiers or guerrillas. Gary sometimes wrote a letter home by asking a buddy to let him use his back as a writing surface. Letters often had smudge marks from dirty hands and writing that revealed that the soldier was exhausted.

Somehow, Gary made time to also write to a few of his closest friends.

Kensel Headrick shared a letter Gary wrote to him in the Spring of 1968 from Vietnam. Gary wrote: "Thanks for writing it sure is good to hear from my friends back home. Things are pretty rough here. Whatever you have to do, do not come over here."

Johnny Waters remembers his very pleasant surprise when he received the first letter from Gary in Vietnam. Gary told him about some of the tough fire fights his unit had engaged in. They began to correspond regularly. Johnny said "the contents of his letters grew more sober and his concerns for his life increased. I got the distinct impression that he had slowly resolved his fate to a higher being."

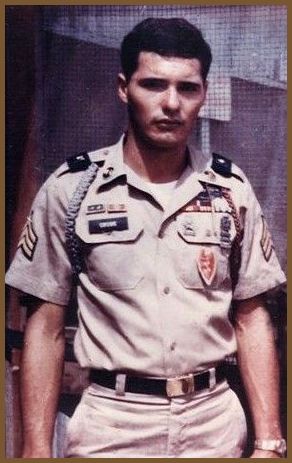

Once in Vietnam Gary attained the rank of Sergeant shortly before he was killed.

Because he was wounded in three different engagements, Gary was awarded three Purple Hearts. For serving in Vietnam he was authorized the National Defense Service Medal, The Vietnam Service Medal, and the Vietnam Campaign Medal. He also was awarded an Army Commendation Medal and a Bronze Star.

A month after his death, Gary Cruse was awarded the Silver Star (General Orders 6507, dated 20 September 1968), "for gallantry in action." He "distinguished himself by heroic action on 18 August 1968, while serving as a rifleman with Company D. 2nd Battalion, 27th Infantry in the Republic of Vietnam. While established in an ambush site, Company D came under intense enemy attach. With complete disregard for his own safety, he immediately began laying down a protective base of fire to enable his platoon to withdraw to a more fortified position. He remained in his now exposed position until his platoon had safely withdrawn. As Cruse was trying to rejoin his command, he was mortally wounded..."

Gary's friend, Kensel Headrick, said of this award: "I get my feathers ruffled when the word ‘hero' is thrown around and applied to anyone wearing a uniform, doing their normal job. Clearly ‘hero' is a special word that should be given only those people who knowingly put themself in harm's way in situations that are life-threatening or worse, to protect the lives of their fellow mankind. This award clearly documents that Gary Cruse was a Hero and I am honored to have known him and proud that he was my friend."

Murray County Historian Tim Howard, whose parents, Jim and Odetta Howard, ran a store on Highway 225 south of Spring Place, recalls that three of the Murray men who died in Vietnam, traded at the Howards' store. Tim knew and liked them because all three picked on him, treating him as a very young buddy. Tim said "though I was only 7 years old, I will never forget the day the news came about Gary. The Army guy that was going to inform the Cruse family stopped at our store to get direction to their house." That was August 19, 1968.

Gary's mother, Maebell, recalls, "I normally would get up, put on my house coat and cook breakfast. But that morning I had a strange feeling and for some reason I dressed before I started to cook breakfast. As I started through the house I heard a knock on the front door and I knew what it was for. When I opened the door and saw the man I simply said ‘No!' He answered, ‘Yes.' I do not remember anything he said or did after that."

The Army man told Mrs. Cruse that Gary had been killed by small arms fire on August 18, in Tay Ninh Province. His body had been recovered and would be brought back to Murray County as quickly as possible. Thirteen days later Gary's body arrived in Chatsworth.

The Department of Defense listed Gary Cruse as Casualty Number 31,660 of the Vietnam War. Less than 13 months earlier, Jimmy Cagle's death had been Casualty Number 13,894. This indicates that 17,766 American servicemen had died in that 13 months!

Two other men from Gary's Company D died in the same fire-fight. Sergeant John Russell Millikan, age 21, was from Quakertown, Pennsylvania. Private First Class Martiniano Valentin, Jr., age 20, hailed from Cambria Heights, New York. They undoubtedly knew each other.

Four more soldiers, from Company A, 3rd Battalion, probably also were killed in the same fire-fight. Sergeant James Clyde Kraynak, age 22, had lived in Connellsville, Pennsylvania. Sergeant Kenneth Lionel Krom, age 21, had called Walkersville, Maryland home. Private First Class Roy Dallas Lowe, Jr. Age 20, was from Charlotte Court House, Virginia. Specialist Four James Ray Moncrief, age 20, listed his home as Cordova, Alabama.

An additional four soldiers appear to have been killed in the same province on the same day, August 18, 1968, because they were supporting the 25th Infantry Division, same as all of the other soldiers named above. Specialist Four Ronald Mathias Heinecke, age 23, had entered the service from Theresa, Wisconsin. Sergeant Randolph Charles Kett, age 21, hailed from Tampa, Florida. Private First Class Lorenzo Sewell, age 18, the youngest soldier to die in this day of intense fighting in Tay Ninh Province, came from Sayreton, Alabama. Private First Class Arturo S. Zamora, age 20, called Mathis, Texas, home.

How sad that so many soldiers, many of whom probably knew each other, died on that same day in Tay Ninh Province, South Vietnam, so far from their friends and families. Sadder still, a total of 77 American service men from Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy died in that single day.

Shocked and deeply saddened classmates, friends, and neighbors paid their respects at Gary's funeral. He was buried at New Hope - Kilgore Cemetery with full military honors.

Several years later, Gary's close buddy, Johnny Waters, honored Gary by personally paying to have the MCHS field house remodeled and named for Gary Cruse. Johnny said "Gary gave his life for our country and he damn well deserved to be recognized and remembered for his gift to this country." Gary Cruse Field House seems an appropriate honor for Sergeant Cruse.

Coach Frank Ross clearly remembers that Gary "was one of the best halfbacks in this area. He always gave 110% to anything he did."

Ross said, "I can remember as well as if it were yesterday, Gary came by the gym as he was departing for Vietnam. He thanked me for coaching him. We talked for a long time. I thanked him for having been someone that reacted so well to coaching. I reminded him that in his senior year our team had a good record, due in no small part to his athletic ability. I wished him well, we said goodbye, then he departed."

For the record, Gary Cruse, in his senior year, led the Murray team to win second place in the region. He was chosen the Most Valuable Player that year.

Coach Ross reminisced that players and coaches were a very close knit group, much akin to family. He said that "we were all devastated at the news of Gary's death. Even though we can never repay those fine, young men like Gary, who gave their lives to defend out country, we can keep them and their families in our thoughts and prayers, and never forget them." A coach who can recall so vividly a halfback from nearly 45 years ago has done exactly that.

Gary Robert Cruse is on Panel 48W, line 40, of the Vietnam Memorial Wall.

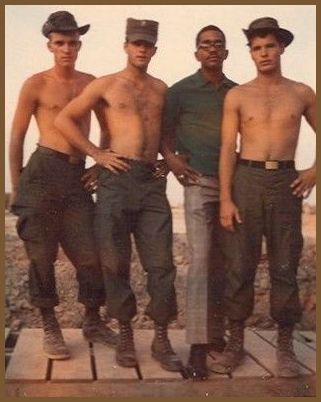

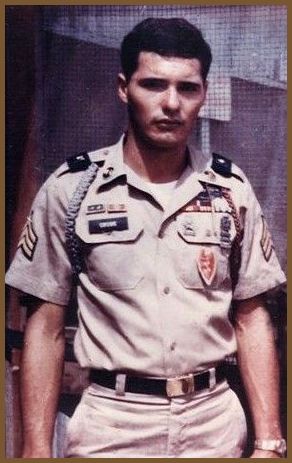

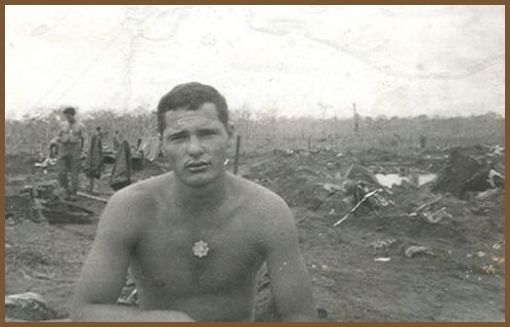

Following photos: Very young Gary Cruse with younger brother Doug; Gary the Halfback; Gary in khakis showing off his new sergeant's stripes; Gary in fatigues; Gary on right end, with 3 buds in ‘Nam; Gary exhausted; and his tombstone.

NEW MATERIAL IN 2011

On Friday, May 20, 2011, Gary's mother, Maebell, received a telephone call from a man named Tom Bowes in Chicago. Mr. Bowes explained that he had been Gary's platoon leader in Vietnam until about three weeks before Gary was killed.

He was calling because he would be driving to Florida over the weekend and wanted to visit Gary's grave. He said that he had contacted the VFW Post in Dalton asking where Gary had been buried and whether any of his immediate family was still alive. How surprised he must have been to hear that Gary's mother is still alive!

Mr. Bowes told Mrs. Cruse that he would be at Gary's grave around 6 p.m., Sunday, May 22nd, and, if she felt like it, he'd like for her to meet him there.

Kensel Headrick, who had been a very close friend to Gary, drove Mrs. Cruse to the cemetery. There they found Mr. Bowes, accompanied by VFW Post Commander Ed Kinney and his wife.

They visited briefly, shared photos of Gary, and Mr. Bowes told some of his memories of Gary. He told them that he had been Gary's and remembered well that they had a good NCO cadre, that they worked well together and with him.

Bowes provided names of some of the soldiers in Maebell's pictures, men whose identities previously she had not known. He also provided current contact information for one he had thought was with Gary during his last couple of minutes.

He said that Gary had been a good rifleman and always wanted to know why we were doing something or going to some particular place. Answering Gary's questions helped Bowes keep the platoon on track.

He smiled when he said that Gary and some of the others southerners sometimes joked that the unit just had too many Yankees in it.

On a more somber note, Mr. Bowes concluded: "When you are in combat, there is a bond built, like a "Band of Brothers." You don't forget the people you served with, particularly those who died. That's why I wanted to stop at Gary's grave."

Gary Cruse's mother, Maebell, with Tom Bowes, Gary's Platoon Leader in Vietnam.

MORE.....2011

The man that Mr. Bowes thought had been with Gary when he died happened to live in South Georgia. Turned out that Kensel Headrick had already planned to drive to Florida early in July so he decided to contact that man and arrange to meet him.

Here is Kensel's report on that visit with a Vietnam buddy of Gary Cruse:

"Last weekend while on my way to Fernadina Beach, I stopped to visit Terry Ballentine. Terry, you may remember, served with Gary Cruse in Vietnam. Terry was the first to reach Gary after he was wounded and, in fact, was still holding Gary when he passed away. It was clearly very painful for Terry to relive that fateful night.

He said that it was about 11 pm when they encountered 200 to 250 NVA regulars. In the ensuring firefight Gary was the point man and made the decision to hold his position while his platoon recovered to a better position. In doing so, he gave cover fire as they regrouped, but his actions left virtually no way for him to rejoin his men. He made the decision, with only a couple of months left in Vietnam, to protect his friends. Of those who knew Gary, the recounting of his actions will probably not be a surprise. Unfortunately, the war in Vietnam changed all our lives, including the family and friends of those that served."

Return to TOP of page!

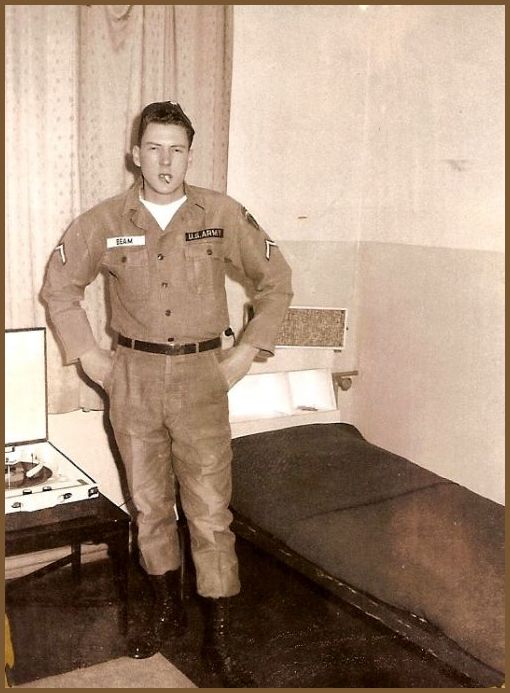

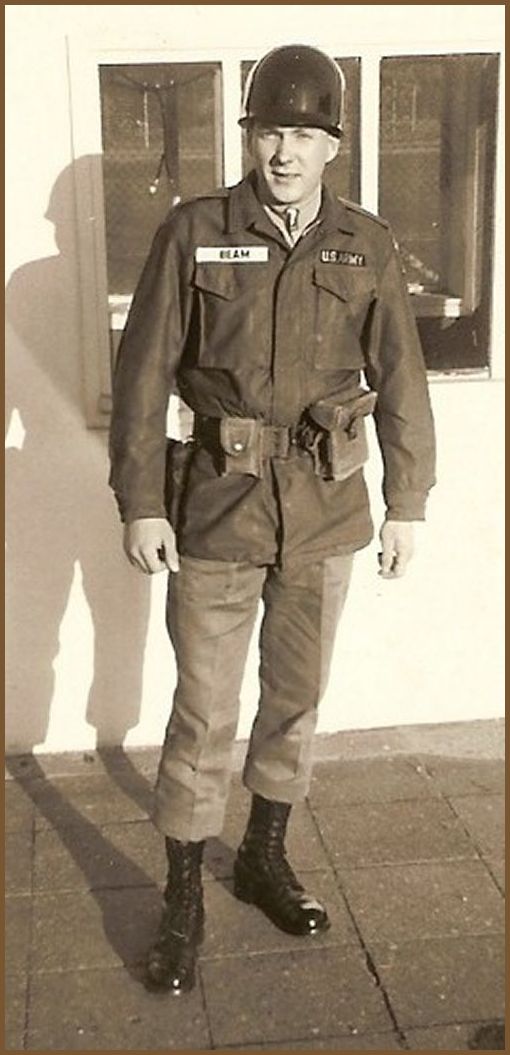

RAYMOND BEAM, LAST MURRAY SOLDIER DIES IN VIETNAM

© Copyright 2010 Herman McDaniel

Pauline Beam Witherow remembers well a conversation from August, 1968. Several members of the Prince Albert Beam family were sitting in the yard as darkness approached, discussing the news that had shocked Murray County that day. The Army had notified a neighbor that their son, Gary Cruse, had been killed in Vietnam. He was the third Murray Soldier to die in that conflict.

Pauline's brother, Raymond Beam, had just been deployed to Vietnam. News of Gary Cruse's death made the Beams realize that Vietnam was a far more dangerous place than they might have earlier thought.

As the conversation neared a close, Raymond Beam's mother, Ada, told them with sadness, "we're probably going to have to go through the same thing ourselves." Afterwards some of the Beams wondered if their mother might have had some sense that Raymond was going to be killed.

Less than a month after that conversation, on Friday, September 13, 1968, Raymond Beam was killed by multiple fragmentation wounds in South Vietnam's Pleiku Province.

Mrs. Beam was home alone when the military man came to officially notify her of her son's death. Since she had no telephone, and did not have transportation, she asked the official if he would drive her to Dalton so she could tell two of Raymond's sisters working at Barwick Mills. He told her that he would do that, but that first he had to notify Raymond's widow.

The two stopped to notify Raymond's wife, Dolores, then proceeded to Dalton's Barwick Mills.

The Army listed Raymond Beam as casualty number 32,884 of the war.

In a surprisingly short time the Army returned Raymond's body to Murray County, in a traditional, sealed, flag-draped coffin. The family buried Raymond, with military honors, in Robinson-Kilgore Cemetery.

On Memorial Day, 2010, even though Raymond had been dead more than 40 years, his military unit, the 35th Infantry sent a soldier to place a tribute on Raymond's grave. Clearly his death had not been forgotten.

Raymond's Early Years

The Beam family lived near present-day 225, on a road now known as Prince Beam Road. His father, Prince Albert Beam, had married Ada Elmira Emberson. Raymond was the sixth of nine children born to the couple. They were (in birth order): Roy, Marvin Albert, Bud, Wilma Jean, Dorothy Mae, Raymond, Ethel Irene, Effie Pauline, and Claude.

Raymond's grandparents on his dad's side were Malcom Beam and Dora Emmalyne Hinson. His mother's parents were John Henry Emberson and Mettie Pruett.

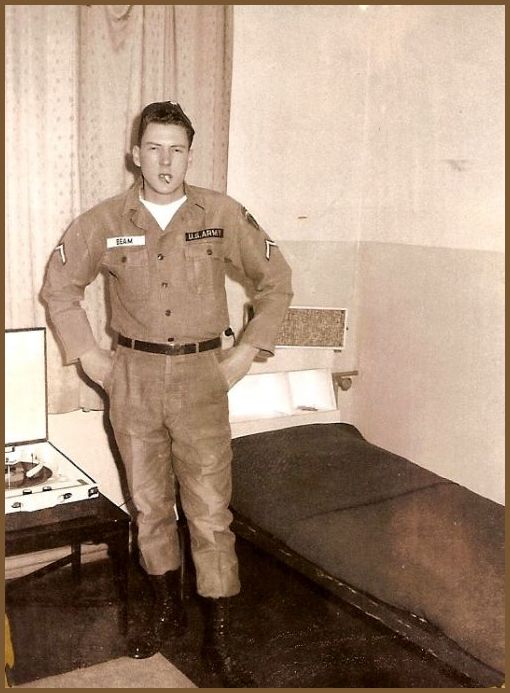

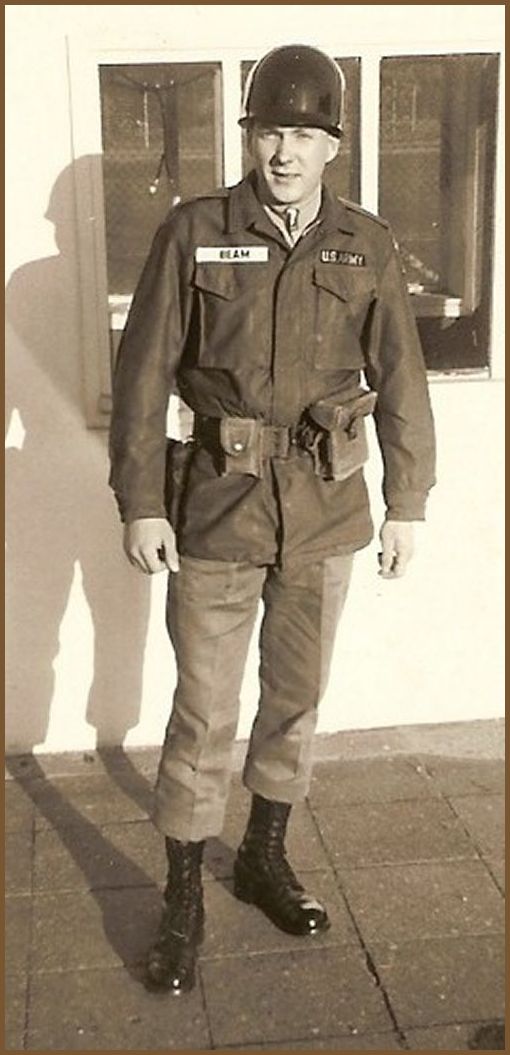

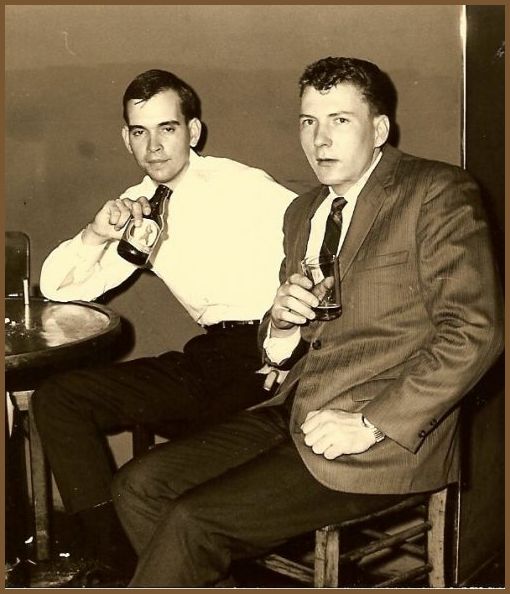

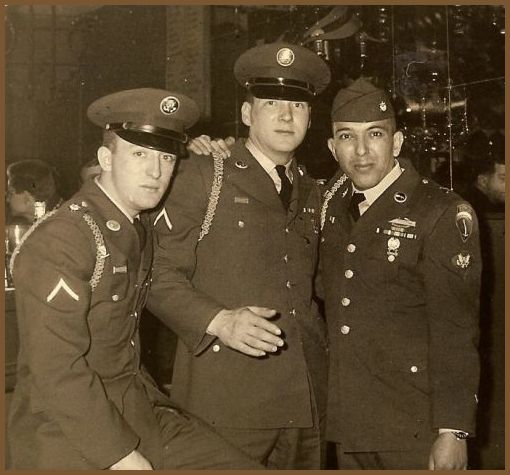

Raymond's family lived in a typical farmhouse of that era, too small for the family, and always needing repairs that they often could not afford to make.